Olga Chernysheva’s work to date consists mainly of shorter videos and of photographic series. Even her paintings and drawings are usually based on moments observed through a lens. Yet this pronouncedly visual and episodic oeuvre is embedded in a long Russian tradition of narrative art.

Nikolai Gogol is its unsurpassed master. His dark and twisted portraits of the people whose bumbling largesse and petty scheming made autocratic power possible in the 1830s and ’40s stand out for their unflinching truthfulness. Gogol’s stories, gathered in collections such as Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka and in in the unfinished novel Dead Souls, are shot through with lucid details that subvert the hierarchies of genre, ignore the decrees of time and space and sabotage the political technology of character-building. With refined simplicity, he would pin down two officials by comparing their faces to ‘one turnip with the tops down and another with the tops up’.

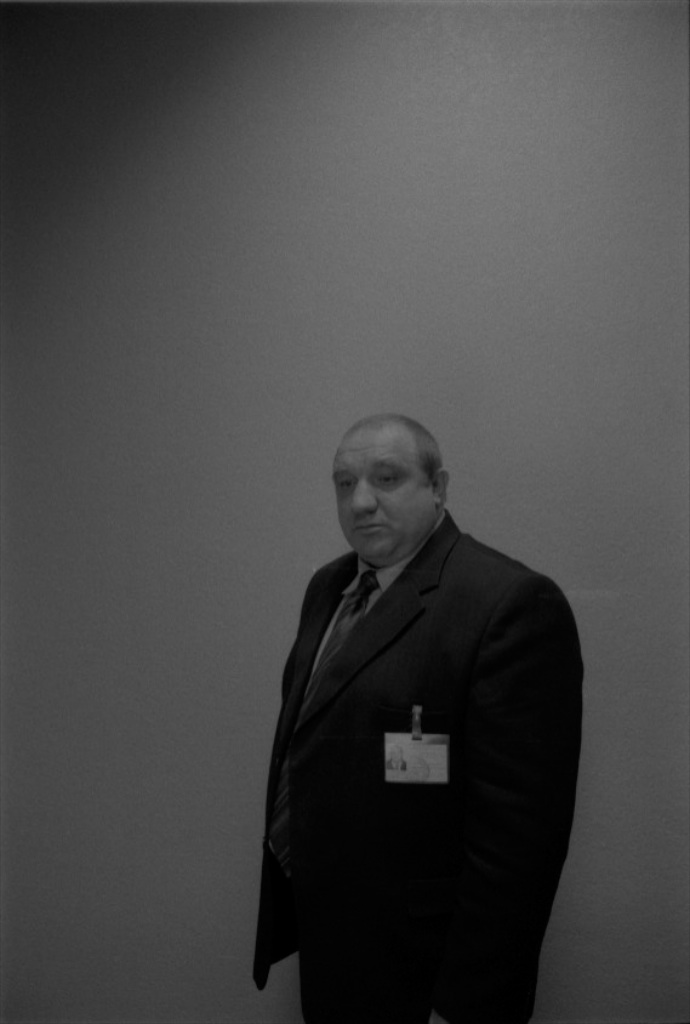

Olga Chernysheva, black-and-white photograph from the the series Guards, 2009

For the last ten years or so, Chernysheva has chosen to portray contemporary Russia, or perhaps it has chosen her. Like Gogol, she is no outsider, at least not only an outsider. Her Russia is also autocratic, also inhabited by souls who struggle to stay alive. They could be sleep-walkers, doppelgänger or only partly human, but they deserve to be seen by a finely attuned eye.

These images of Russian humanity can be found in Gogol too, and both artists strive to protect the notion of individual subjectivity by keeping it open to flashes of the sub-human and the super-human. If there is detachment, there must also be empathy. If there is disgust, there must also be delight. Above all, there must be understanding, conveyed to audiences in densely composed packages of tone and gesture and attitude.

Olga Chernysheva, black-and-white photograph from the series Guards, 2009

In Guards (2009, 6 black-and-white photographs shown as prints on transparent film, dimensions variable) Chernysheva shows some of all the men employed by institutions and companies in Moscow to illustrate the idea of protection, of making the city ‘undangerous’ as the Russians put it.

She explains: ‘Especially in Moscow it is very typical for guards to wear a badge with their photograph on the chest. So you always see two faces simultaneously, as you would see the Roman double-faced Janus, who was also connected with guarding, since he was the god of entries and exits.’

Olga Chernysheva, black-and-white photograph from the series Guards, 2009

The guards seem almost weightless, about to drift off, so absorbed are they by looking at everything and nothing at the same time, projecting a possible sudden outburst of violence and impassively surrendering to a milky meditative haze. What counter-action would these dormant agents stage if their ‘object’ came under attack?

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video The Train, 2003

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video The Train, 2003

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video The Train, 2003

The Train (2003, video, 7’30”) is one of Chernysheva’s best-known works. The Andante from Mozart’s Piano Concert no.21, which accompanies black-and-white footage assembled to represent the passage through a train in motion, is not an after-thought or a device to sweeten the image of the Russian everyday. Instead it establishes the emotional logic and visual rhythm of the cut before the topic of travelling, or more precisely of travellers, can emerge.

Musicality is a defining feature of Chernysheva’s art. With gentle determination, she moulds evidence of unscripted life into an audio-visual sonata, a train of thought picking its way through the forgettable routines of early Putin-era Russia. The sole moment to contradict the image of persistent disillusion is when fellow travellers give some money to the wandering half-blind bard, possibly a retired schoolteacher, who has memorised a lesser-known Pushkin stanza eulogising the would-be independent seclusion of the gentleman poet.

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video Festive Dream, 2005

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video Festive Dream, 2005

In another video, Festive Dream (2005, 7′), Chernysheva is exploring the problem of visualising the imaginary through the real. She does it by deftly cross-referencing two competing streams of early Soviet cinema: the self-reflexive experiments of authors like Dziga Vertov (is the slumbering drunkard on the bench not a wink to the well-dressed woman sleeping rough in The Man with the Movie-Camera?) and the Hollywood-style phantasmagoria of Stalin’s favourite film-makers, Grigory Aleksandrov and others.

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video Festive Dream, 2005

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video Festive Dream, 2005

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video Festive Dream, 2005

The ordinary citizen’s dream of communism was always in the future tense: plenty of food and drink even in the shops, people finding time for dancing and playing, full bodily satisfaction. In Soviet cinema, such excesses had to be staged with an entire film crew. Today, Chernysheva would argue, it is enough to travel a few miles outside of Moscow with a video camera. But ready-made coffins are displayed next to the vodka and wrapped sweets in the village shop…

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video Marmot, 1999

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video Marmot, 1999

A cruder, yet complex image of Stalin’s afterlife is found in Marmot (1999, video, 2’30”). A woman in a man’s fur hat, looking not much older than 50, is fidgeting with her things before re-joining a street demonstration of old-school communists. We know that after the collapse of the USSR such manifestations gather mostly marginal types. Chernysheva spends a few moments outlining a character for this demonstrator; a sketch carrying the promise of nuance. Gradually we become fully aware that her portable icon is a portrait of Stalin.

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video March, 2005

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video March, 2005

March (2005, video, 7′) could also be read as political commentary. The use of pre-pubescent uniformed cadets and gum-chewing pom-pom girls as live decorations for an unidentified but apparently lacklustre ceremony encapsulates the vulgarity of today’s Russia, where the political is all but abolished, but intrusive politics nevertheless taints all aspects of life.

People’s time, their physical presence and mental compliance, comes at a grossly reduced price. The sergeant says: ‘Thank you for your service, cadets!’ To which they answer in unison: ‘I serve Russia.’ Once again we are reminded that the rhythmic articulation of detailed observation is Chernysheva’s preferred artistic method.

Olga Chernysheva, still from the video L’Intermittence du coeur, 2009

The newest video, L’intermittence du coeur (2009, 3′), was shot on celluloid as a pointedly faithful copy of the painting Encore, again encore! by Pavel Fedotov, a mid-nineteentth-century career officer who became an independent painter but ended his life in a mental asylum. We must imagine a young officer stationed somewhere in the proverbial ‘Province X’ of the Czar’s Empire, with nothing but his poodle’s tricks to intellectually engage him.

In Chernysheva’s version 2009 meets 1850 halfway. A fugue by Fedotov’s contemporary Mikhail Glinka provides the soundtrack and the phrasing for the film, while the log cabin’s window has become a half-dead television screen. The scene probes the poetic potential of bored solitude. Could it unexpectedly liberate us? Chernysheva comments: ‘I use a French title; it is from Proust. He says that our soul can never attain richness as a whole, only by intermittence.’

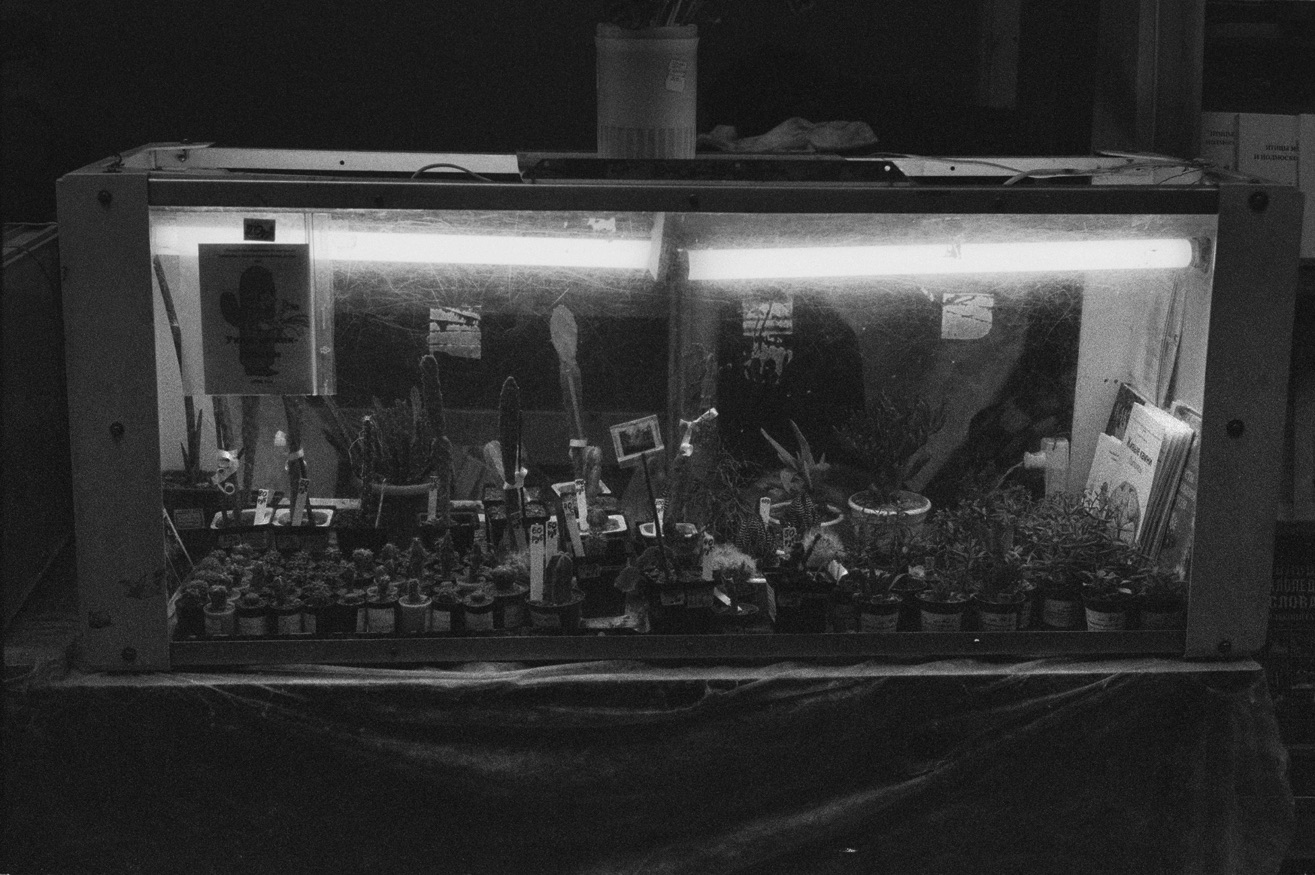

Olga Chernysheva, from the series The Cactus Seller, 2009, black-and-white photograph in lightbox, 45 × 30 cm

Olga Chernysheva, from the series The Cactus Seller, 2009, black-and-white photograph in lightbox, 30 × 45 cm

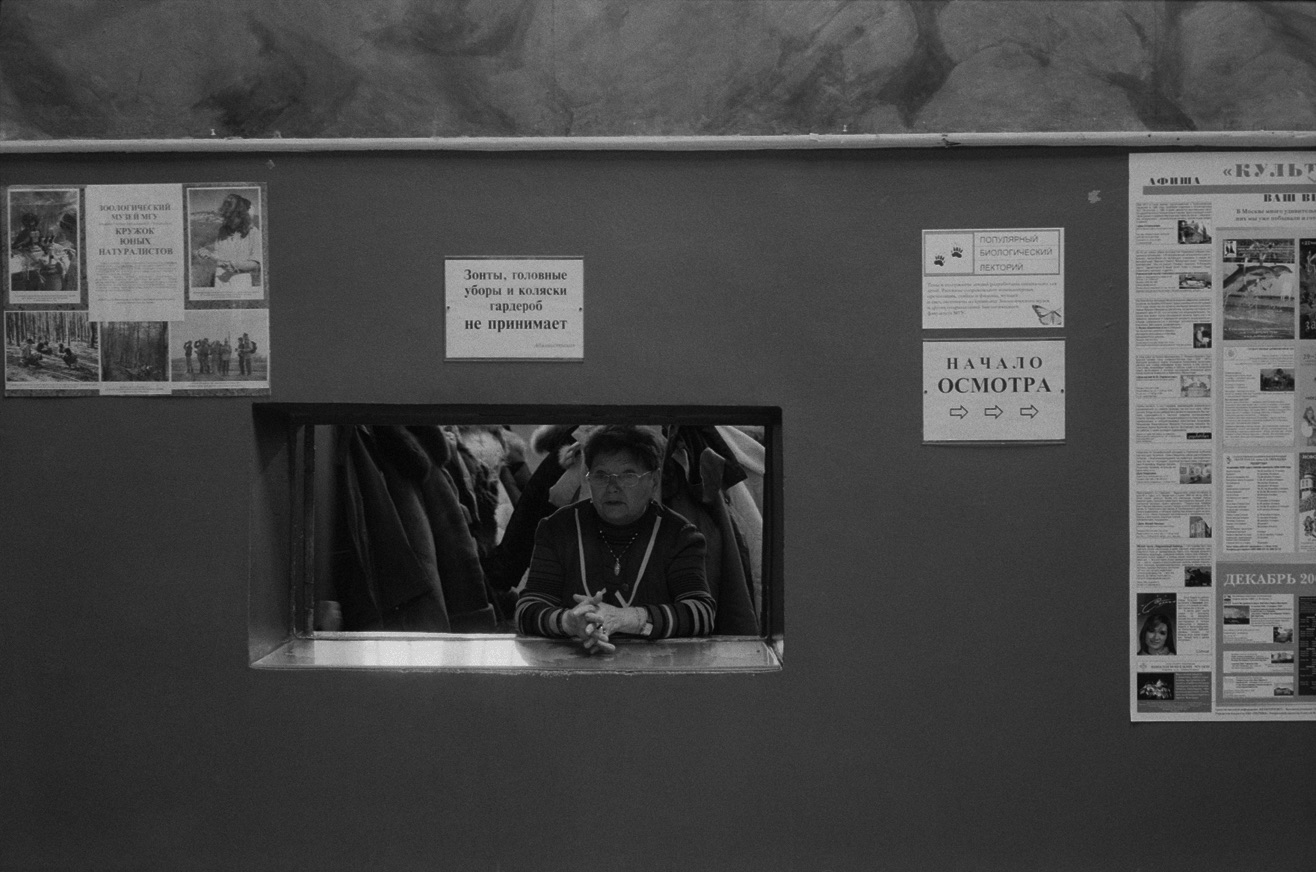

Another new work is Cactus Seller (2009, 33 black-and-white photographs in lightboxes, each 30 × 45 cm). Chernysheva often works with image sequences, where meaning is accumulated through the juxtaposition of details but individual shots can be left unexplained, uninhibited by a rational narrative programme. This seemingly aimless photographic walk through Moscow’s Zoological Museum may or may not have happened in reality.

The entrance hall with its pedagogical frescos and the exhibits with their well-edited captions radiate dark, enigmatic energy. The cactus seller at the entrance, pretending to see nothing but his illuminated display cases, may hold the key to the whole story. This is what Chernysheva claims in her title and display. But it might as well be the guard with the philosopher’s beard, who spends his days frozen in a contemplative attitude under the fire hydrant in the reptile gallery.

Olga Chernysheva, from the series The Cactus Seller, 2009, black-and-white photograph in lightbox, 30 × 45 cm

Olga Chernysheva, from the series The Cactus Seller, 2009, black-and-white photograph in lightbox, 30 × 45 cm

Olga Chernysheva, from the series The Cactus Seller, 2009, black-and-white photograph in lightbox, 30 × 45 cm

Such are the characters that populate Olga Chernysheva’s works. They are her Russians, and much like Gogol she lets them stay in half-darkness most of the time. She gives no full and balanced account of their value to other people, their accomplishments and shortcomings, their obsessions, their enjoyment. Instead she lets a sudden ray of light fall on an aspect of their mental constitution that they themselves would never have thought about.

Anders Kreuger

Text adapted from an essay published in the booklet for Olga Chernysheva’s exhibition ‘Local Exercises’ at Yapi Kredi Kültür Sanat Yaymcilik, Istanbul, 9 September – 11 October 2009, curated by René Block.