I’m not drawn to grand narratives. I’m more interested in accuracy of presentation and elasticity of form.

– Yane Calovski interviewed by Başak Şenova, 20121

This essay inaugurates Kohta’s new series ‘Appraisals’, dedicated to artists in our exhibition programme. The series will offer critical appraisals of their achievementsand relate their interests and intentions to contemporary art as a global constituency of individuals and communities, thought and action, form and truth.

We will aim to perform ‘the action or act of estimating or assessing the quality or worth of something or someone’, which is how the Oxford English Dictionary defines the second meaning of appraisal.

The first, older and more tangible meaning of the wordis given as ‘the action or act of setting a price on or estimating the monetary value of something’. This is not an active concern for us, but we can never fully anticipate the side effects, in social and economic life, of our intellectual undertakings.

Installation view of ‘Yane Calovski: Personal Object’ at Kohta, left to right: Personal Object, 2018 (part 1: iron, makeup); Bed, 2020, plastic foam; Personal Object (part 2: synthetic rubber, iron, makeup). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jussi Tiainen

The immediate reason for launching our new series with an analysis of Yane Calovski’s practice from the late 1990s until now is his exhibition ‘Personal Object’ at Kohta. It opened to the public on 11 March 2020, closed because of Covid-19 on 17 March, reopened on 2 June and will remain open through 2 August.

‘Personal Object’ was too modest in scope and size to function as a mid-career retrospective. This is usually a much more ambitious exercise in taking stock of an artist’s oeuvre, and also a tool for looking ahead at the ‘not yet said, not yet done’ (to quote the title of a series of paintings by Nina Roos, the artist next in line for an exhibition and an appraisal).

This text will try to do what the exhibition specifically didn’t aim for, namely to situate Calovski’s practice and oeuvre in a wider context. So there seems to be no way around the artless initial gesture of establishing some factual coordinates.

Installation view of ‘Yane Calovski: Personal Object’ at Kohta: Embroidery, 2020, birch- and aspenwood, paint. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jussi Tiainen

Yane Calovski was born in 1973, in Skopje, which was then the capital of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, one of the six constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and is now the capital of the Republic of North Macedonia, which became an independent state in 1991. (‘North’ was added only in 2019, when a long conflict with Greece over the name was finally resolved.)

Now based in Skopje and Berlin, Calovski was educated in the US, where he graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia in 1996 and from Bennington College in Vermont in 1997, and where he started his career as an exhibiting artist.

Installation view of ‘Yane Calovski: Personal Object’ at Kohta: Closet, 2020, detail of Panel 3 showing Drawing 3:1 (Red Face), 2017, ink on paper, 30 × 21 cm; Nine Principles of Open Form, 2017, gouache and type on two sheets of mineral paper, each 32 ×23 cm; Drawing 3:2 (Embroidery by My Mother), ca 1972/2020, cotton on wool, 35 × 70 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jussi Tiainen

Calovski’s continued education has included longer research residencies at CCA Kitakyushu in Japan in 1999–2000 and at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht, the Netherlands, in 2002–2004. Since the turn of the millennium, he has exhibited widely across Europe and on other continents.

In 2015, he represented Macedonia at the 56th Venice Biennale in collaboration with his partner in life, the artist Hristina Ivanoska, with whom he has also been running Press to Exit Project Space in Skopje since 2004.

Besides working as an artist, Calovski is an active and proactive member of Macedonian civil society and the elected president of Jadro (‘core’ or ‘nucleus’ in Macedonian), an association of the independent cultural scene in North Macedonia that Press to Exit Project Space and thirteen other organisations founded in 2012. His focus as president has been to lobby for improved working conditions and equal opportunities within the independent scene and for civil–public partnership and collaboration.

Installation view of ‘Yane Calovski: Personal Object’ at Kohta: Phrase, 2020, ink and carbon transfer on rice paper, 10 sheets, each 30 × 40 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jussi Tiainen

Most of the time, Calovski’s work can truthfully be described as composite or hybrid.

Drawing has been a consistent presence in his practice since he was a student, but installation – specifically the organisation of space and of images and objects in space – is also a recurrent preoccupation. So is performance, understood as enactments in various kinds of environments, either emphatically designated for art practice or purposely blending into non-art reality.

We shouldn’t let the pragmatism and modesty of the introductory quote lead us to believe that Calovski avoids the grand or the narrative. Nor should we assume that he, in his attentiveness to the elasticity of form, refrains from researching and referencing history (including recent art history) or from enacting politics.

Studies for Under Usden, 1997, ink and gouache on transparent paper, ca 30 × 45 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: the artist

Calovski may, in fact, be more versed in real-life politics than most other artists, and certainly than many of those who specialise in political art as a genre.

He knows, from experience, the exhilaration and despondency of activism and advocacy, and how persuasion and perseverance are stress-tested in actual encounters with the powers that be, in negotiations that may drag on for years.

He knows, also from experience, the rewards and drawbacks of working alone, in intimate constellations of peers and in the battlefields of collective action.

Installation view of Under Usden at Bennington College, Vermont, 1997, wood, house paint. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: the artist

As a result of his American schooling and early immersion in the globalised contemporary art system, Calovski soon absorbed the insights of late post-war modernism. Inevitably he also discovered its inherent tensions and conflicts, many of which were succinctly articulated by Theodor W. Adorno in Aesthetic Theory (unfinished when he died in 1969, first published in German in 1970).

‘Art is the social antithesis to society, not directly deducible from it’, Adorno writes,2but also ‘the artistic subject is inherently social, not private’3 and ‘the mediation of the transsubjective is the artwork’.4

The book is a product of its time, or rather, of previous times that had shaped Adorno: the lost era of a Jewish German-language high culture that upheld an ambitious aesthetic regime but remained suspicious – even dismissive – of the bourgeoisie that fostered it.

Study for Under Usden, 1997, gouache and ink on rice paper, ca 30 × 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: the artist

We may, for instance, find it rather useful to ponder what Adorno meant by insisting on the ‘truth content’ of artworks and splicing together phrases like these:Aesthetic Theory may still be of service to us today, as we try to reclaim the still functioning parts of its quintessentially European outlook for a world that no longer can, nor ought to, take it entirely seriously.

That artworks fulfil their truth better the more they fulfil themselves: this is the Ariadnian thread by which they feel their way through their inner darkness.5

Installation view of ‘Yane Calovski: Personal Object’ at Kohta: Closet, 2020, detail of Panel 5 showing Drawing 5:8 (The Wonderful World That Almost Was, after Paul Thek), 2000, pencil on paper, 8 sheets, each 25 × 35.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jussi Tiainen

Adorno’s quest for truth content is in no sense idealistic. We shouldn’t banalise it by insisting that there can only be plural (i.e. postmodern or postnormal) truths. We shouldn’t discount his appreciation of darkness as standard Cold War-era angst. Adorno may guide us today, as we feel our way through a new darkness to find a new meaning of truth.

One of Calovski’s recurrent references is Paul Thek (1933–1988), the fluid and influential American artist, exiled in Europe for years: eclectic and ephemeral, pictorial and processual and pedagogical, a master of the light touch and of dark truths who died with an AIDS diagnosis and whose work was collected by the Catholic church.

I Said I Was. I Never Said I Was, 2019–ongoing, book project, 800 numbered and printed pages, each 29.7 × 21 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Here is what Calovski himself has to say about Thek:

There was a lot to admire and appreciate, not to copy as a style, but basically to remember. […] The more I learned about him, the more I understood about my own insecurities and myself.6

Although Adorno doesn’t mention him, and probably wouldn’t have understood or appreciated his work had he known it, Thek’s continued relevance for Calovski resonates with the notion of truth content, however abstract and high-strung that may seem today.

We shall keep both Adorno and Thek in mind throughout our account of Calovski’s practice. It shaill be organised in four chapters, interlocking but also distinct, discussing his personal or solo work, his inter-personal or duo work (mostly in collaboration with Hristina Ivanoska), his research-based work and his enactment-based and organisational work (also mostly with Ivanoska).

The House and Its Imperfections 1/4, 1997, ink, gouache and xerox photo transfer on rice paper, ca 90 × 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: the artist

Chapter One: Personal Work

It is always changing. It has order. It doesn’t have a specific place. Its boundaries are not fixed. It affects other things. It may be accessible but go unnoticed. Part of it may also be part of something else. Some of it is familiar. Some of it is strange. Knowing of it changes it.

– Robert Barry, Art Work, 19707

For appreciating an artwork, is the person behind it of any consequence? Should we regard the work as a vehicle for the person, or vice versa?

The individual, the personal and the subjective are not the same, in art and elsewhere, but we can and ought to make room for all of them in any account – or appraisal – of an artist’s trajectory.

It we wish our analysis to make sense within a broader understanding of art and society, we are well advised to focus on the artwork as a function of all-encompassing inter- or trans-subjective mediation. Adorno, of course, has an aphorism about it:

Today immediacy of artistic comportment is exclusively an immediate relationship to the universally mediated.8

The House and Its Imperfections 2/4, 1997, ink, gouache and xerox photo transfer on rice paper, ca 90 × 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: the artist

We should remind ourselves of this mediatedness whenever we consult an artist’s personal biography to illuminate his individual works, but then again we can’t draw a satisfactory map of the inter- or trans-subjective in his practice and oeuvre without first locating the subjective.

Calovski’s career as an emergent artist was kick-started when The House and Its Imperfections was shown in New York, first in Sideshow Gallery in Brooklyn and then in the exhibition ‘Selection Fall 1998’ at the Drawing Center.

The series of four large ink drawings on glued-together strips of industrial rice paper was made during his studies at Bennington, which included architecture, literature and anthropology, as an attempt at synthesis between sculpture and architecture.

The House and Its Imperfections 3/4, 1997, ink, gouache and xerox photo transfer on rice paper, ca 90 × 120 cm. Private collection, New York. Photo: the artist

The House and Its Imperfections 3/4 (detail), 1997, ink, gouache and xerox photo transfer on rice paper, ca 90 × 120 cm. Private collection, New York. Photo: the artist

The drawings are based on the floor plan, elevation, aerial and area views of his childhood home on the outskirts of Skopje. His father, the prominent poet and radio journalist Todor Calovski, had it built in the early 1970s, without an architect and without blueprints. A colour-coded wooden maquette of the house is also part of the overall work, which borrows its title from a short poem by Todor Calovski:

The repairman enters a hill of gleaming shadows

With a firm intention to transform the wall

the lonely emptiness of the window

the narrowed transparency of the balcony

There is love in his hands

surpassed fear in his tools

and unyielding peace when he says:

‘First you build, then you repair’

We count the changes: me

my wife

my children

and we seethat our house gradually loses

the strange sense of its imperfections

which we so much discussed late in the nights.9

The House and Its Imperfections 4/4, 1997, ink, gouache and xerox photo transfer on rice paper, ca 90 × 120 cm. Private collection, Philadelphia. Photo: the artist

The House and Its Imperfections 4/4 (detail), 1997, ink, gouache and xerox photo transfer on rice paper, ca 90 × 120 cm. Private collection, Philadelphia. Photo: the artist

The House and Its Imperfections marks the beginning of Calovski’s engagement with drawing in the public realm. It retroactively applies conventional visual systems for documenting the intentions behind a built structure, and then breaks this illusion by introducing illusory elements, such as the view through a window of the furnishings in a room, or pictorial traces of remembered actions in and around the house.

In this way, Calovski reintroduces a pre-modern practice that art historians call value perspective, highlighting our perception of what it considers to be the most important things: architecturally, visually, emotionally. It allows the work to tell the story both episodically and epically, and to cast a modest family home as an image of perfection.

After the exposure of The House and Its Imperfections at the Drawing Center, the Philadelphia Museum of Art acquired a large drawing from a subsequent series that continued to develop similar themes.

Installation view of Nevermind the View at Villa Stanze, Manciano (Tuscany), 2003, rice paper screen, camera obscura lens. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Richard Torchia

Installation view of Nevermind the View at Villa Stanze, Manciano (Tuscany), 2003, found photographs, drawings, self-designed furniture, rice paper screen with camera obscura projection. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Richard Torchia

The rice paper strips reappear, now as a hanging screen ready to capture rays of Tuscan sunlight filtered through a camera obscura lens that yield images of a distant landscape, in the work Nevermind the View at Manciano, Province of Grosseto, in the warm summer of 2003.

Stanze, the villa where this composite installation was staged, had been the local headquarters of the Fascist Party before the war, and then for years a social club for railway workers, but it was abandoned for Calovski to ‘squat’ within the framework of an exhibition project titled ‘Quattro Venti’.

The works appraised in this chapter are labelled solo projects because Calovski must be fully credited for them artistically, but they often also involve collaborators from various fields.

To Manciano he brought two fellow artists. Ricard Torchia contributed the two camera obscura lenses: one focusing on the balcony just outside the smaller room in the villa, the other powerful enough to transmit views from the seaside 40 kilometres away onto the screen in the larger room. Sebastian Menendes helped to make recordings of environmental sounds from these two areas of uptake.

Nevermind the View, 2003, camera obscura projection onto rice paper screen. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Richard Torchia

Nevermind the View, 2003, camera obscura projection onto rice paper screen. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Richard Torchia

Nevermind the View was not only the spectacle, waiting to happen at any moment, of people and buildings and trees and the sky caught ‘in the act’ and turned upside-down as light-images onto gently fluttering rice paper; it was also the contrast between the shuttered and sunlit versions of the installation.

Both were rooms with a view, but the views were different. Darkness brought out the projection of the outside world, while light made it possible to see drawings and calligraphed texts (also on rice paper) pinned onto a wall and some old black-and-white photographs of railwaymen socialising scattered on a makeshift table.

Installation view of Nevermind the View at Villa Stanze, Manciano (Tuscany), 2003, ink on paper, found black-and-white photographic prints, self-designed furniture. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Richard Torchia

Installation view of Nevermind the View at Villa Stanze, Manciano (Tuscany), 2003, found black-and-white photographic prints. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Richard Torchia

This work, painstakingly put into place and seen by very few, radiates truthfulness in its approaches to the paper and lenses and sound equipment used, to the building and its obscure history, to the landscape and the light breeze outside, to drawing as the gesture that gathers these elements together – but also as a unifying note that doesn’t quite hold, ‘like the little crack when your voice breaks’.10

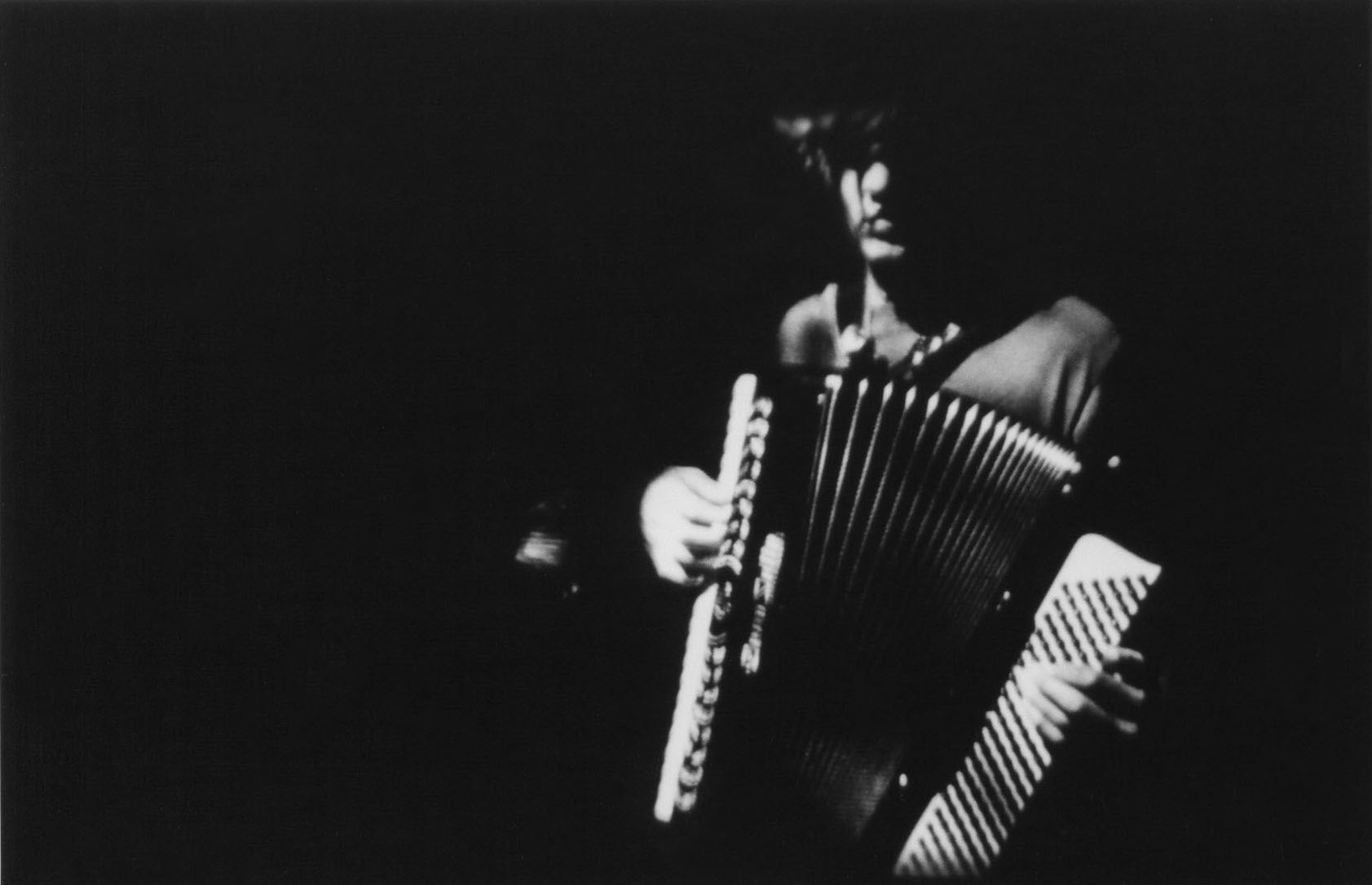

Live performance by Sebastian & Sebastian and Tobias Sjöberg during the opening of ‘Everything Is after Something‘ at the Baltic Art Centre, Visby (Sweden), 2004. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Baltic Art Centre

Live performance by Sebastian & Sebastian and Tobias Sjöberg during the opening of ‘Everything Is after Something’ at the Baltic Art Centre, Visby (Sweden), 2004. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Baltic Art Centre

The following summer Calovski found himself working in another classical holiday getaway: the Swedish island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. The result of his production residency at the Baltic Art Centre in Visby, Everything Is After Something, is an instructive example of how he integrates various practices and references into a composite whole driven by the mutually enforcing desires for articulation and construction, formulating a multi-layered message and delivering it on a purposely designed platform.

Let us unpack what this meant, in real terms, for Everything Is After Something.

The practices called upon were those of drawing (four large and predominantly figurative compositions in ink and gouache on paper), film-making (a silent black-and-white 8mm film), music (a live performance at the exhibition opening by Swedish band Sebastian & Sebastian, with the artist Tobias Sjöberg playing the accordion and singing a song written for the occasion), architecture (a platform, with variously raised levels, on which the entire project was exhibited) and research (the process of creating all the work’s components was documented in a xeroxed artist’s book).

Everything Is after Something, 2004, stills from 8mm film, transferred to DV, 2’30”. Courtesy of the artist

The references animating the work ranged from the hybrid legal status of the small uninhabited island of Ar, a disassociate Swedish territory previously part of Gotland’s extensive defence infrastructure (in the film and the artist’s book) to the text piece Art Work (1970) by American conceptual artist Robert Barry (used with his permission as the lyrics for the song), Robert Smithson’s aerial footage of Spiral Jetty (1970) and Walter de Maria’s Two Parallel Lines (1968), also known as Mile Long Drawing (again in the film, with its aerial footage of small islands surrounding Gotland, and in the artist’s book).

In retrospect, the inclusion of Robert Barry’s text, and not least its rearticulation as song, is perhaps the most pertinent aspect of Everything Is After Something (a title referring to the practice of referencing) and at the same time the most prophetic, pointing forward to Calovski’s collaborative and research-based work practice in the years to come.

The four large drawings seem less concerned with research, but they do function as a storyboard for the entire project, perhaps even as a mood board channelling its wider personal and art-specific meaning.

Everything Is after Something 1/4, 2004, ink on paper, 100 × 200 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

Everything Is after Something 2/4, 2004, ink on paper, 100 × 200 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

Everything Is after Something 3/4, 2004, ink and gouache on paper, 100 × 200 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

Everything Is after Something 4/4, 2004, ink and gouache on paper, 100 × 200 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

When Kohta invited Calovski for another production residency in Helsinki in the winter of 2020, one of the points of reference was the scale and ambition of that series of drawings from 2004.

Another reference was the work Personal Object (2017–2018). In its first incarnation it consisted of two metal hooks, a tongue-like piece of pulled synthetic rubber, brown foundation makeup that had belonged to Calovski’s late mother, Biljana Calovska, and a pane of milked glass from a building in downtown Skopje put up as part of the reconstruction after the devastating earthquake on 26 July 1963.

Yane Calovski, Personal Object, 2017–18, synthetic rubber, iron, recycled glass, makeup, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Vase Amanito

The modestly sized sculptural installation embodies the strand in Calovski’s practice that this chapter tries to elucidate. He is at his most personal when he pulls together practices and references, alone or in collaboration with friends and fellow artists, into works and installations that are simultaneously environments, events and experiences.

To him, the artist appears to be interchangeable with the metteur en scène, the French term for a theatre and film director that literally translates as ‘the one putting things on stage’. And when his work is explicitly about image-making or objecthood, it remains composite and hybrid to its core.

Another potentially helpful extract from Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory reads:

The subjective experience directed against the I is an element of the objective truth of art.11

Installation view of ‘Yane Calovski: Personal Object’ at Kohta: Embroidery, 2020. Aspen and birchwood, paint. Dimensions variable; Closet, 2020, drawings and objects from different years on five sliding plywood panels. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jussi Tiainen

Calovski’s residency in Helsinki resulted in an exhibition that treats mediations of the personal as an exercise of auto-fiction – not in the sense of practicing a skill but in the sense of exercising a right.

Embroidery (2020) is a dominant presence in Kohta’s main gallery: a construction of wooden sticks and plates, all painted black, and at the same time a drawing in space, the prototype for an architectural folly, an invitation to linger and sit down. It was also a reinterpretation of a small embroidery, in cotton on wool, of abstract triangular and rectangular shapes made by Biljana Calovska sometime in the early-to-mid 1970s.

Closet (2020) is in itself a mini-retrospective, a selection of drawings from the last 20 years pinned onto five plywood panels that were, in turn, mounted on the wall like sliding closet doors. It was as if viewers found themselves inside the closet looking out, through the medium of drawing.

Untitled (front cover of pilot issue for D Is for Drawing magazine), 2004, gouache on black paper, 35 × 25 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Untitled (back cover of pilot issue for D Is for Drawing magazine), 2004, gouache on black paper, 35 × 25 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Drawing is, as we may already have concluded, crucial to Calovski’s practice, especially when he dips into the stream of the the personal. Yet no constant stream of drawings is flowing from his hands. In fact he uses the medium rather sparingly, as a precision tool for transforming a multitude of concerns into readable images. Perhaps we could say that drawing, for him, is directedness rather than directness.

In Calovski’s practice drawing also serves to connect the personal with the inter-personal and the societal. During his time at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht, he launched the journal D Is for Drawing, which brought together reproductions of work by fellow artists and essays on drawing and its continued relevance. Only three issues of the journal could be printed: no. 0 in 2004 (designed by Melissa Gorman), no. 1 in 2006 and no. 2, a collaboration with the Berlin-based magazine Fukt, in 2007.

The initiative points ahead to other collaborative creative projects and institution-building ventures. These shall be discussed in the following chapters. First we shall look at Calovski as a member of creative duos.

Yane Calovski and Naya Frangouli, Common Denominator (Idealpolitik), performative action outside the National Museum, Ljubljana, 2000. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Naya Frangouli

Chapter Two: Inter-Personal Work

this detail

becomes

a picture

this picture becomes

a reason to

separate the initial pose

from the final picture

the final print

– Yane Calovski, 201512

Do artists (and curators) gain or lose by collaborating with their peers? Although their quest for control may be dismissed as out-dated and irrelevant in the hyper-networked production and marketing niche that is the contemporary art world, the question is neither irrelevant nor easy to answer.

While sharing responsibilities and rewards of ideas and their realisation is a powerful engine for many, claiming all attention for your own brand still makes sense for artists (and, again, curators) who wish to thrive in the so-called attention economy – although a more honest term would be ‘distraction economy’.

Some artists find that the advantages of joint thought and action trump those of unambiguous attributability, and not only for projects with a pronounced social or political agenda. Calovski has consistently produced and exhibited work as a partner in a creative duo, usually but not always with Hristina Ivanoska.

Yane Calovski and Naya Frangouli, Common Denominator (Idealpolitik), performative action outside the National Museum, Ljubljana, 2000. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Naya Frangouli

Calovski got to know Greek artist Nayia Frangouli in Japan, where they both participated in the international research programme for young artists at CCA Kitakyushu and where they were invited to participate in the third edition of the itinerant European biennial Manifesta in Ljubljana in 2000.

Only in 2019 could the conflict with Greece about the name Macedonia be resolved. In Italian, the name can also mean a ‘fruit salad’ because of the many ethnicities that once inhabited the Ottoman province over which the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 were fought. Since then there has been a Province of Macedonia in northern Greece.

‘As people, generally speaking, we don’t trust each other; we are a bit paranoid’, Calovski and Frangouli state in the catalogue for Manifesta 3.13

Yane Calovski and Naya Frangouli, Common Denominator (Realpolitik), 2000, CD case, 12 × 12 cm. Courtesy of the artists

On the street outside the two artists had put up a stand and were handing out apples from Macedonia and oranges from Greece, all with the same sticker: the Vergina Sun, a symbol (radiating golden rays on red ground) of the ancient Kingdom of Macedon used as the national flag for the Republic of Macedonia in 1992–1995. Common Denominator (Idealpolitik/Realpolitik) (2000), their joint work for Ljubljana, took place in and around the National Gallery of Slovenia. A compilation CD with ten nationalist songs about the same land, five each in Macedonian and Greek, was playing inside the museum’s stairwell.

The co-authors of Realpolitik sought to bypass, and thereby de-escalate, simmering conflict through the sharing of ‘something as simple, yet voluptuous, as fruit’.14 Their work was resuscitated for an exhibition in Thessaloniki in 2016 but the original CD was, unfortunately, stolen in Skopje.

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Nature and Social Studies: Spiral Trip’ at the Contemporary Art Centre, Skopje, 2003. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Mila Ivanovska

Calovski and Ivanoska, who had known each other as teenagers, reconnected in 2000 and started working together almost immediately. Nature and Social Studies: Spiral Trip (2000–2003), their first creative collaboration, encompassed both process and product, both lived reality and referenced tradition.

The artists made a spiralling trip, mostly by car, from the geographic centre of Macedonia at Izvor to Skopje. We find a succinct description by Richard Torchia in his essay for the catalogue of the exhibition summarising the project and, incidentally, marking the end of programming at the Contemporary Art Centre Skopje:

After months of preparation, Ivanoska and Calovski departed Izvor on May 14 and returned to Skopje on May 20, 2002, extending a 73-kilometre drive that would ordinarily take an hour into a week-long road trip covering more than 800 kilometres.15

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, topographical model of Macedonia for ‘Nature and Social Studies: Spiral Trip’, 2003, cardboard, ca 12 × 12 × 16 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: the artists

Their project referenced American art history – Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and Walter de Maria’s New York Earth Room (1977) – as well as Macedonian schoolbooks of the socialist era (the ‘nature and social studies’ of the title), current indie pop (the Scottish band Belle & Sebastian), fashion advertising (from Purple magazine) and, not least, the tense political situation in Macedonia, where armed conflict broke out in 2001.

If the trip was ‘a physical drawing’, as Torchia suggests, or a tracing of Spiral Jetty onto the map of Macedonia, the exhibition was dominated by a schematic cardboard model of the republic’s mountains and valleys, a re-enacted Earth Room.

The central and lasting feature of Spiral Tripas a finished work was a series of six drawings, jointly executed by Calovski and Ivanoska during a residency at Yadoo in Saratoga Springs, Upstate New York. The drawings read like a road movie, with dramatic violent incidents, but also as a roman à clef about the pleasures and tensions of living and working together.

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Nature and Social Studies: Spiral Trip 1/6, 2001–2002, graphite and colour pencil on paper, 71 × 105 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Nature and Social Studies: Spiral Trip 2/6, 2001–2002, graphite and colour pencil on paper, 71 × 103 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Nature and Social Studies: Spiral Trip 3/6, 2001–2002, graphite and colour pencil on paper, 50 × 70 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Nature and Social Studies: Spiral Trip 4/6, 2001–2002, graphite and colour pencil on paper, 100 × 100 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

If Spiral Trip was a work immersed in the ongoing life of its authors and protagonists, Calovski’s and Ivanoska’s next substantial collaborative project, Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art (2007) was rooted in the historical past, referencing Skopje’s destruction in the earthquake of 1963 and the international solidarity mobilised to rebuild it.

This work – first exhibited at Kronika, the municipal art gallery of the industrial city of Bytom in southern Poland in the summer of 2007 – also explicitly belonged to a future that could have been: the visionary proposal for a Museum of Modern Art that the architect Oskar Hansen (1922–2005) submitted in 1966 to the Polish authorities in charge of getting this museum built and donating it to the people of Skopje.

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art 2/12, 2007, ink-jet print on Fabriano acid-free paper (edition of 10 + 2 AP), 100 × 70 cm. Courtesy of the artists

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art 3/12, 2007, ink-jet print on Fabriano acid-free paper (edition of 10 + 2 AP), 100 × 70 cm. Courtesy of the artists

Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art 4/12, 2007, ink-jet print on Fabriano acid-free paper (edition of 10 + 2 AP), 100 × 70 cm. Courtesy of the artists

Hansen (who was of Norwegian-Russian origin, born in Helsinki and active in socialist Poland after the war) wanted the museum to be continuously transformed for different exhibitions and events. His structure would have consisted of numerous hexagonal platforms, hydraulically lifted and lowered to form new constellations depending on the museum’s programming needs and folded away when unused.

The proposal was rejected and instead a moderately brutalist glass-and-concrete building, designed by a group of architects known as the Warsaw Tigers (Wacław Kłyszewski, Jerzy Mokrzyński and Eugeniusz Wierzbicki), materialised in 1970 on an imposing hill not far from Skopje’s largely intact Ottoman-era old town.

When Polish curator Sebastian Cichocki was first invited to Skopje by Calovski and Ivanoska in 2004, before he became Director of Kronika, no one in Skopje seemed to be aware of Hansen’s utopian museum, designed not only to host new art but also to inspire and provoke it into action. Cichocki managed to procure a copy of the blueprint from Hansen before he passed away in 2005.

Installation view of the full series of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art, 2007, at the City Art Gallery, Ljubljana, 2015. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Matevž Paternoster

This visualisation of Hansen’s idea of open form inspired Calovski and Ivanoska to make a series of twelve posters, in collaboration with graphic designer Ariane Spanier, for exhibitions and discursive events that could have taken place at Oskar Hansen’s MOMA. They feature Ana Mendieta, Susan Sontag, Mladen Stilinović, Paul Thek and others.

Curator Elena Filipović writes, in her essay for the Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art catalogue:

In the end, Calovski’s and Ivanoska’s posters chart out a past we could never have taken part in, but they do so without making it a simplistically retrospective or nostalgic endeavour (and the final poster in the series, set already into the future, slyly insists on this). Their conditional perfect would have beenis meant to prepare us all the better for what still could be, instigating us to question our present’s future and the museum and art’s role in defining it.16

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Wayside (A Performance Yet to Happen)’ at Tobačna 001 in Ljubljana, 2019, left to right: Institutional Drawing (Rok Vevar), 2019, wall paint, height 177 cm, length variable; Visual Exercises (Colour Theory), 2018–19, gouache, pigment and graphite on Colorfix Original archive paper, each 32.5 × 24.9 cm; four posters from Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art/Nine Principles of Open Form, 2018–19, 10 ink-jet prints on acid-free paper (edition of 10 + 2 AP), 100 × 70 cm; one poster from Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art, 2007, ink-jet print on Fabriano acid-free paper (edition of 10 + 2 AP), 100 × 70 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Andrej Peunik

It is instructive to compare Hansen’s modular and fluid museum concept, virtually unknown in what used to be called the West, with the ideas that Pontus Hultén developed for Moderna Museet in Stockholm around the same time, in the late 1960s, and partly realised at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, which Hultén directed in the 1970s.

Hultén visualised his model for a contemporary art museum as four concentric circles: the surrounding society (information); tools for processing this information (workshops); information that has been processed (artworks in exhibitions); the best of this processed information (the permanent collection). All of which was to be accessible in both physical and cybernetic space, in the museum and on computers.17

In the catalogue, Calovski is quoted as saying:

The crumbs are only possible if they are shed from an existing whole. I do believe that revealing only some and not all crumbs makes for an interesting articulation of how we address information and how we want to see history reinterpreted.18

This amounts to a pocket-sized manifesto for research-based art, which shall be the topic of our third chapter. But first we must look at other high-profile and internationally visible exhibitions that Calovski and Ivanoska have made together.

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘We Are All in This Alone’, Macedonian pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale, 2015, pencil, gesso and gold paint on wall; ink on paper; graphite on paper; acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Sara Sagui

They represented Macedonia at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, with an installation titled We Are All in This Alone and occupying a small but visible space on the first floor of the newly converted Sale d’Armi in the Arsenale.

Başak Şenova was the curator of the exhibition and the editor of the catalogue. In her introductory essay she writes:

The project references a number of intricate sources: a fresco painting from the church of St Gjorgi in Kurbinovo painted by an unknown author in the twelfth century, as ell as writings by Simone Weil, Luce Irigaray and recently discovered personal notes by Paul Thek dating from the 1970s. While searching for political values in the representations of formal aesthetic and literary sources, the work carries a specific urgency to articulate ways in which we continuously engage and disengage the past and present, questioning the notion of faith within socio-politics and economic realities.19

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘We Are All in This Alone’, Macedonian pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale, 2015, pencil, gesso and gold paint on wall; ink on paper; graphite on paper; acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Sara Sagui

Calovski’s and Ivanoska’s previous collaborations had been predicated on shared ideas and intertwined working processes and produced seamlessly inter-personal results.

As the title itself indicates, this changed with We Are All in This Alone. Today both artists usually present a selection of their solo work in a jointly conceived setting with some jointly executed elements.

For this collaboration, which began as the exhibition ‘Chapel (We Are All in This Alone)’ at the Kunsthalle Baden Baden in 2014 (curated by Ksenija Cockova), the joint setting was a scaled-down and pared-down representation of St Gjorgi, in which the wall areas covered in frescoes were rendered in burnished gold: a monochrome ‘master drawing’ that makes space for other drawings.

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘We Are All in This Alone’, Macedonian pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale, 2015, pencil, gesso and gold paint on wall; ink on paper; graphite on paper; acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sara Sagui

In the chapel thus reconstituted, Ivanoska hung drawings and image-objects quoting texts by Weil and Irigaray, while Calovski displayed drawings based on Paul Thek’s rediscovered correspondence with his Paris gallery, kept in the Egidio Manzona collection in Berlin, and two empty icon boards primed with white gesso but unpainted (or, to be precise, once painted and then erased).

As a prelude to the pavilion, Calovski’s video Detail (2015) reintroduces an ambiguity usually purged from readings of the original Kurbinovo frescoes. Was their anonymous author really a male master? Why couldn’t these flamboyant images have been painted by a young woman?

Seductive black-and-white footage of Calovski smoking a cigarette, shot during his time in Japan, is overlaid with the lines of a poem written specifically for the work (and quoted at the beginning of this chapter).

Detail appeals, again, to the qualities Calovski finds attractive in Paul Thek: ‘this duality, this escapism and falling into your own trap’.20

Yane Calovski, Detail, 2015, still from video, black-and-white, no sound, 17′. Courtesy of the artist

Calovski’s and Ivanoska’s Macedonian pavilion illustrated (i.e. ‘cast light upon’) how a non-academic reading of theory and history may transform itself into an ensemble of works foregrounding image and object, narrative and space on their own terms.

Both Calovski and Ivanoska have, in their solo and in duo practices, invested thought and production resources into understanding two distinct roles that artists have been able to play after artistic practice was generally hybridised in the ‘relational turn’ of the 1990s: the artist as researcher and as stage director.

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2018–19, with Unspoken, 2015, three canvases, textile colour, pigment, graphite and thread on linen, each 330 × 151 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Vase Amanito

We will return to Calovski’s progress through these two approaches, but first we will see how the duo used them, in a recent exhibition trilogy, to renegotiate their practices both retroactively (reconfiguring existing works for three different locations) and proactively (trying out emergent interests).

The series, curated by Branka Benčić from Apoteka – Space for Contemporary Art in the town of Vodnjan in Istria, Croatia, consisted of three individually titled exhibitions: ‘Prologue (A Form of a Question)’ at Apoteka in 2017, ‘Dialogue (A Form of an Answer)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 2017–2018 and ‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje in 2018–2019.

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2018–19, left to right: Visual Exercise, 2018, from series of nine text-based drawings, graphite and gouache on Colorfix Original archive paper, each 32 × 24.8 cm; Visual Exercise (Colour Theory), 2018, from series of twelve colour-based drawings, gouache and colour pencil on Colorfix Original archive paper, each 32 × 24.5 cm; Visual Exercise (Method for Initial Determination), 2018, from series of three drawings, graphite, colour pencil and gouache on Bristol paper, each 28 × 21.6 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Vase Amanito

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2018–19, left to right: Visual Exercise (Shell, Divided and Banner 1: Open, Formed, Unbuilt), 2018, metal, paint, cotton and graphite, structure 78 × 176 × 37 cm, fabric 200 × 100 cm; Visual Exercise, 2018, from series of nine text-based drawings, graphite and gouache on Colorfix Original archive paper, each 32 × 24.8 cm; part of Yane Calovski’s Shell, Divided, 2011/2918, 38 × 128 × 37 cm; Visual Exercise (Colour Theory), 2018, from series of twelve colour-based drawings, gouache and colour pencil on Colorfix Original archive paper, each 32 × 24.5 cm. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Vase Amanito

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2018–19, parts of Yane Calovski’s Shell, Divided, metal, paint, total structure 379 × 257 × 285 cm, and To Fold Within as to Hide, 2015/17, handmade synthetic rubber, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Vase Amanito

‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ filled the two largest halls in the Skopje museum, the first of which was configured as another tribute to Oskar Hansen, the author of the museum that never was.

The main presence there was Nine Principles of Open Form (2018) a joint work by Calovski and Ivanoska interpreting Hansen’s writings and his architectural and pedagogical practice centred on life as communality and art as organic process. It combined ten posters in a typeface designed by Ivanoska with a series of ‘visual exercises’: Bauhaus-like permutations of coloured circular shapes on found coloured paper backgrounds hung just above a 90-centimetres-tall skirting of concrete-grey wall paint.

Installation view of Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2018–19, Assembly of Spirits, 2018, wall paint, dimension variable. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Vase Amanito

In the second hall another joint work, the wall painting Assembly of Spirits (2018), was executed on the only concrete surface of an otherwise windowed inner courtyard, its ghostly shapes fluttering over a brutalist screen.

The more spacious second hall was also where Calovski’s Personal Object, which was already discussed, was premiered, as well as his work Mulichkoski’s Bench, Divided (2018), which will be discussed towards the end of the next chapter.

Jointly and separately, Calovski and Ivanoska put the conditions of art into play, grounding the textual in the visual and vice versa. It is as if they want to help art overcome itself by concentrating on everything that is specific about it: material, production process, the story and history of the place it inhabits and of art as a protocol of knowledge, understanding and attitude.

Installation view of Master Plan, 2008, in ‘Manifesta 7: The Rest of Now’ at Alumix in Bolzano/Bozen (Italy), left to right: Yane Calovski, Master Plan, series of 66 drawings, pencil, ink and gouache on paper, each 27 × 20.2 cm; Kenzo Tange and Asociates, four-part maquette of proposal for the reconstruction of Skopje, 1965, , balsawood, glass, plastic, three surviving parts, each 100 × 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of the City of Skopje. Photo: Manifesta 7

Installation view of Master Plan, 2008, in ‘Manifesta 7: The Rest of Now’ at Alumix in Bolzano/Bozen (Italy), Kenzo Tange and Asociates, four-part maquette of proposal for the reconstruction of Skopje, 1965, , balsawood, glass, plastic, three surviving parts, each 100 × 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of the City of Skopje. Photo: Manifesta 7

Chapter Three: Research-Based Work

He is like an archivist dealing with one messy archive, persistent in his effort to keep things messy while finding something extraordinary that, at least for a moment, will shine a new light on an old story.

– Hristina Ivanoska on Yane Calovski, 201521

In the last 20 years, artistic research has gone from being a progressive proposal on the fringes of the art world and academia to becoming so institutionalised that it sometimes feels like a threat to the future of art. This is true of the ‘art education complex’ and also, although to a lesser extent, of the ‘art exhibition industry’.

Real problems appear when formalised research becomes a parallel career track for artists, when only artists with a doctoral degree are eligible for professorships in fine art and when terms that make sense in academia, such as ‘research hypothesis’ and ‘knowledge production’, are uncritically adopted by the mainstream art world – and by its funders.

Research as a modus operandi for artists is a different matter: an integrated part of an their development and career and a quest for insight founded in a personal or systemic need. That is the sense in which the term will be used throughout this chapter.

Master Plan 38, 2008, ink on paper, 20.2 × 27 cm. Collection of Deutsche Bank, Frankfurt am Main

Master Plan 13, 2008, pencil and gouache on paper, 27 × 20.2 cm. Collection of Deutsche Bank, Frankfurt am Main

Around 2005, when Calovski returned to Skopje after almost fifteen years abroad, he began to take an active interest in the master narrative of his native city: its post-earthquake reconstruction under the auspices of the United Nations and the master plan that won the international competition, designed by Japanese ‘metabolic’ architect Kenzō Tange (1913–2005).

It may be said that the task wasenvisioned by capitalists (in the UN), articulated by socialists (Yugoslav functionaries) and carried out by communists (Warsaw Pact countries funding specific building projects). While such organised international solidarity remains a remarkable feat, the story of the reconstruction is also one of compromised ideals and inadequate realisation.

Less than 20% of Tange’s master plan was realised, including the idea – but not Tange’s actual design – of high-rises forming a ‘wall’ around the core city and the integrated Transportation Centre for train and bus links, completed only in 1981.

Since the declaration of Macedonia’s independence ten years later, Skopje has become disfigured not just by the usual wear and tear of post-socialist capitalism, but also by the ‘antiquisation’ inflicted on public buildings and spaces during the decade of nationalist governance in 2006–2016, when the rebuilding programme ‘Skopje 2014’ was launched.

Kenzo Tange and Asociates, three surviving parts of four-part maquette of proposal for the reconstruction of Skopje, 1965, , balsawood, glass, plastic, three surviving parts, each 100 × 100 cm. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of Skopje. Photo: Robert Jankuloski

The backdrop to Calovski’s research on Skopje is therefore not a soft afterglow of utopian internationalism, as we might assume when we admire the intricate wooden maquettes of Tange’s master plan, but harsh disillusion, caused by a lack of both hindsight and foresight that seems to be a universally local phenomenon.

We have already seen how Oskar Hansen’s unbuilt museum inspired Calovski and Ivanoska to imagine a counter-factual history of their city through programmes and events that could have happened but didn’t.

In 2008 Calovski located the first of Tange’s three maquettes of the master plan for Skopje, the winning proposal from 1965. It was kept in the Museum of the City of Skopje but hadn’t been properly inventoried and one of the original four parts (representing the Transportation Centre) was lost, possibly used as firewood by a janitor in the 1980s.

Obsessive Setting 48, 2010, pencil on paper, 27 × 20.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Obsessive Setting 33, 2010, pencil and gouache on paper, 27 × 20.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Calovski had the surviving parts of the finely crafted model transported to a former aluminium factory in Bolzano, South Tyrol, where it was exhibited as part of Manifesta 7 (curated by the Raqs Media Collective). It was accompanied by 66 drawings of three kinds: redrawn period photographs of architects working on the reconstruction of Skopje, coloured maps of their plans for the new city and unclassified abstract shapes. There was also an artist’s book with texts by Calovski and photographs of Tange’s maquette.

In the book, titled Master Plan like the installation, Calovski refers to the desire for a future ‘society of citizens and forms’ as the ultimate horizon of Skopje’s regeneration.22 He has continued to work with the archive of this venture in a number of works to date: Obsessive Setting (2010–2011), Shell (2011–2018), Former City (2017–ongoing) and Mulichkoski’s Bench, Divided (2018).

Installation view of ‘Obsessive Setting’ at Żak | Branicka, Berlin, 2010, left to right: Obsessive Setting, 2010, plywood, metal, 200 × 200 × 200 cm; photographs of Kenzo Tange and Associates’ maquette of the proposal for the reconstruction of Skopje, 1965, each 30 × 30 cm; screen with the video Obsessive Setting, 2010, 4’53”, featuring Simon Takahashi. Art Collection Telekom. Photo: Żak | Branicka

By now we have understood how Calovski assembles his work. He enlists various components – self-generated or borrowed from a larger common archive – to stage a situation, always intended to affect viewers intellectually and viscerally, morally and atmospherically, but never to constitute an exhaustive statement or authoritative programme.

This moderate approach to research (and to the socially engaged) in art is perhaps characteristic of the generation of artists who came of age just before the ‘academic turn’ of the late 2000s crashed through art education. Calovski and his contemporaries were schooled to respect that crucial operation in art for which English lacks an appropriate term: Gestaltung, an act of ‘giving-form’ but also of ‘becoming-form’.

But art, mimesis driven to a point of self-consciousness, is nevertheless bound up with feeling, with the immediacy of experience; otherwise it would be indistinguishable from science, at best an instalment plan on its results and usually no more than social reporting.23

We must resist the temptation to regard such statements by Adorno as conservative by default, so tied up with late high modernism as to be irredeemably démodé. If we really care about research as a force of good, then we must do what we can to save research-based art from its own demons.

Shell, 2011, metal, paint, 420 × 320 × 380 cm. Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje. Photo: Vase Amanito

For practicing artists who, like Calovski, need to feed the results of any research (whether basic fact-finding or a more advanced staging of knowledge) into their production but still wish to gain access to the support sometimes offered by academia, the dilemma is this: as soon as the artistic articulation of a material begins, the process no longer counts as research.

Obsessive Setting was a continuation of Master Plan, with drawings fictionalising Studio Tange’s work on Skopje in the mid-1960s and an installation in which the maquette is replaced with a prototype for archiving furniture that includes a sleeping-pod shelf. This is a reference to another metabolic architect, Kishō Kurokawa, and his famous Capsule Tower in Tokyo from 1972, but also an empty stage for a possible performance of archiving (and then taking a rest from the labour it requires).

Shell, in turn, may be described as a three-dimensional drawing of a ‘democratic stage’, a 1:5 gridded steel replica of a reinforced concrete structure from the 1970s in Skopje City Park. The work is divided into eight parts, which may be shown together or separately.

Former City: 22 May 2017, still from video, 2’35”. Courtesy of the artist

Former City: 22 May 2017, still from video, 2’35”. Courtesy of the artist

Former City is a more comprehensive project, undisciplined and as yet open-ended, which started after the fire that destroyed the formerly city-owned Institute for Town Planning and Architecture in Skopje on 21 April 2017. The Institute was where the actual rebuilding of Skopje –– the ‘compromised’ local version of Tange’s master plan – had been plotted and monitored until the demise of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. It was privatised in the 1990s and neglected by the new owners.

Calovski and other volunteers went into the still smouldering building three weeks after the fire and salvaged as much as possible of the once-considerable archive (blueprints, models, reports) that used to be kept in the Institute’s Bunker Room.

The State Archives accepted part of what they managed to pull out of the rubble. Calovski has held on to the rest: charred stumps of folders or photographs, but also project reports with fold-out maps and other typed and printed documents. Some of the material may eventually enter the collection of the Museum of the City of Skopje.

Installation view of Former City, work in progress, 2017–ongoing, at IASPIS Open Studios, Stockholm, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: the artist

Installation view of Former City, work in progress, 2017–ongoing, in exhibition for the international symposium ‘Archiving as an Act of Collective Resistance’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Vase Amanito

Installation view of Former City, work in progress, 2017–ongoing, in the exhibition ‘Incipient Act’ (part of the research project Undisciplined: Construction of an Archive) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Vase Amanito

Installation view of Former City: Wallpaper #1, 2018 at the EVN Headquarters, Maria Enzersdorf (Austria). EVN Collection, Vienna. Photo: Lisa Rasti

These traces of collective memory have become raw material for a series of spatial articulations by Calovski, beginning with tentative displays in early 2018 at the IASPIS residency programme in Stockholm (where the salvaged documents were paired with drawings) and at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje (where they where paired with objects made of synthetic rubber under the title ‘Incipient Act’).

The charred front pages of reports make a special appearance in the work Former City: Wallpaper #1 (2018), commissioned by the EVN Foundation in Vienna for their headquarters.

They – these objects and these various acts of display – have entered the realm of individual artistic articulation, but also that of institutional artistic research. Calovski activates them within a research project titled Undisciplined: A Construction of an Archive, organised by Press to Exit Project Space with partners in Croatia and the Netherlands and with funding from the European Year of Cultural Heritage, a programme part of Creative Europe.

Among the events realised within this framework were an exhibition and an international symposium at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje in the early summer of 2019.

Mulichkoski’s Bench, Divided. 2018, concrete, metal, Styrofoam and pigment (edition of 6), 50 × 520 × 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Vase Amanito

As we remember, Mulichkoski’s Bench, Divided was premiered at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje in 2018. The work aims to achieve two things, and both illustrate the power that research-based art may have when it avoids dogmatic discursivity.

First, it is a commentary on Macedonia’s antiquisation policy. Petar Mulichkoski (born in 1929) is a prominent modernist architect. One of his best-known buildings is the so-called Palace of Administration in Skopje, built in the early 1970s as the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and now the headquarters of the Macedonian government. In 2013, Mulichkoski unsuccessfully fought the nationalist government’s plans to remodel its façades in a ‘neo-classical’ style. The only surviving element of the original ensemble is this bench, designed in 1972, which Calovski replicates.

Installation view from Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, ‘Epilogue (A Form of an Argument)’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2018–19, with Mulichkoski’s Bench, Divided, 2018, concrete, metal, Styrofoam and pigment (edition of 6), 50 × 520 × 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Vase Amanito

Second, the ‘divided’ of the title has both technical and socio-political meaning. Calovski cut the bench in two, so that two thirds of it could be placed inside the museum’s plate-glass wall and the rest outside. The work served two distinct constituencies: the museum’s visitors (many of whom are educated, middle-aged people from the Macedonian-speaking majority population) and visitors to the surrounding hill-top park who tend not to go inside (among whom many are younger and belong to the Albanian- or Roma-speaking minorities).

Ironically, the outdoor constituency took better care of their third of the bench than visitors and staff inside the museum, keeping it clean and intact.

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, synthetic rubber and object from the Bauarchiv: still pipe chair, still pipes with nickel surface and leatherette upholstery, 245 × 31 (43.5) × 5 (36) cm (designed by Marcel Breuer, built ca 1930, original location: Kinderheim Aula, Oranienbaum). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, synthetic rubber. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, synthetic rubber and object from the Bauarchiv: flooring roll (Triolon Bondenbelag), large roll (made ca 1925, previous location: post office in Hesse). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

To Fold Within as to Hide (2015) was made in response to an invitation from the Bauhaus Foundation in Dessau, Germany, to research its archive and participate in the exhibition Haushaltsmesse 2015 (‘Household Fair 2015’, curated by Elke Krassny and Regina Bittner), which sought to unsettle notions such as modernity, growth and domesticity.

Calovski focused his attention on carefully preserved refuse – incomplete furniture prototypes, a roll of used flooring, panes from a dismantled glass ceiling, a fire escape ladder – and used it for a series of installations in all the rooms of the house, designed by Walter Gropius, where the Bauhaus teacher Oskar Schlemmer and his family lived in 1926–1929.

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, drawings (ink on paper) and objects from the Bauarchiv: seven fragments of glass ceiling, each 41 × 42 cm (built ca 1930, possibly reconstructed in the 1980s, original location: Kandinsky/Klee House, Dessau). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, drawings (ink on paper) and objects from the Bauarchiv: seven fragments of glass ceiling, each 41 × 42 cm (built ca 1930, possibly reconstructed in the 1980s, original location: Kandinsky/Klee House, Dessau). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, drawings (ink on paper) and objects from the Bauarchiv: seven fragments of glass ceiling, each 41 × 42 cm (built ca 1930, possibly reconstructed in the 1980s, original location: Kandinsky/Klee House, Dessau). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

To these selections from the archive he added tree series of drawings. The first, on 13 sheets of the Foundation’s office paper, were made in response to mimeographed bulletins from KoStuFra, the Communist Students’ Faction active at Bauhaus before the school was closed by the new Nazi government in 1933. He also displayed three drawings made in collaboration with his then five-year-old son Teodor on typing paper from the 1960s and another three made on paper that his grandfather Metodija had used for household accounts in the late 1940s. Around the time when these works were made, his father Todor Calovski passed away.

Crucially, other works were also added to this context-sensitive ensemble: colourful pieces of synthetic rubber, mixed and pulled under artisanal conditions at Hrisal, a small family enterprise in Skopje. Although made from inorganic industrial materials, they became veritable embodiments of the elasticity of form and brought him as close as Calovski had ever come to the practice and ethos of painting.

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, synthetic rubber. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, synthetic rubber. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

Installation view of To Fold Within as to Hide, transdisciplinary project at the Mulche/Schlemmer House, Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau (Germany), 2015, synthetic rubber and object from the Bauarchiv: fire escape ladder, metal, 245 ×31 (43.5) × 5 (36) cm (built in the 1920s, original location: Laubenganghäuser, Mittelbreite 14, Dessau). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bauhaus Foundation Dessau/Tassilo C. Speler

In the Schlemmer House nothing could be mounted on the walls, so all these elements were placed on floors, draped over doors and staircases, hung inside wardrobes. The overall installation responded to protocols of preservation by animating inanimate objects as agents of history.

Both subtle and bold in its referencing of domesticity, the intervention at the Schlemmer House also reaches out across time to The House and Its Imperfections, created 18 years earlier.

To Fold Within as to Hide may be Calovski’s most successful research-based work. It articulates genuine engagement with a specific body of knowledge (preserved in almost fanatically material form by the Bauhaus Archive) and at the same time incites it to perform in a theatre of Gestaltung, which it conjures out of practically nothing, just by using space in ways that are both intricately coded and completely free.

Tommy Rot, 2002, performative action in public spaces in Bolzano/Bozen (Italy), as part of the exhibition ‘To Actuality’ at ar/ge kunst. Photo: Angelika Burtscher

Chapter Four: Enactment-Based Work

As counter-narratives, enactments are a form of espionage that can re-read or re-write the story line of any situation. In their role as counter-intelligence, enactments could be essentially ethical forms of communication. When well orchestrated, they can disrupt the violence of reality as a finitude of meaning.

– Maia Damianović on Yane Calovski’s Tommy Rot, 201224

In Calovski’s theatre of the personal, the inter-personal and the research-based, where is the ‘actual work’ located?

The question points to a problematic he has courted ever since he started making installations with elements of performance during his studies in the US. Committing to such ephemeral aesthetic formats and opening up his practice to both art-specific and socio-political references, he has consistently resisted the temptation to make the work easily localisable as an object of a certain value or a position of a certain importance.

As Richard Torchia writes:

His critically engaged, context-based practice could be characterised by its tolerance for uncertainty and openness to public reception.25

Tommy Rot, 2002, performative action in public spaces in Bolzano/Bozen (Italy), as part of the exhibition ‘To Actuality’ at ar/ge kunst. Photo: Angelika Burtscher

Calovski’s career could have taken a drastically different turn had he continued to demonstrate his sophistication as a draughtsman when his exhibiting career took off. Instead he chose to experiment with the modes of working we have characterised as inter-personal and research-based.

We have seen how a fleeting constellation of diverse elements, some of them with shared or collective authorship, may constitute the core of a work by Calovski and make it ‘his’ more eloquently and effectively than a display of images or objects conceived and crafted by him alone.

We have also floated the idea of the artist as metteur-en-scène. Now we shall use it to discuss some examples of how Calovski has, in one-off and long-term projects, assumed the responsibilities of the stage director, the curator or the activist.

Sometimes this shape-shifting is clearly part of his identity as an artist. Sometimes – especially when he involves himself in Macedonian cultural politics – he crosses over into awareness-raising and institution-building and becomes another kind of public figure.

Tommy Rot, 2002, performative action in public spaces in Bolzano/Bozen (Italy), as part of the exhibition ‘To Actuality’ at ar/ge kunst. Photo: Angelika Burtscher

Tommy Rot (The Sublime Violence of Truth) (2002–2012) was part of the exhibition ‘To Actuality’, organised in Bolzano in the spring of 2002 by the Vienna-based critic and curator Maia Damianović (who sadly passed away in 2016). The work was conceived specifically for the city, as Damianović explains:

Bolzano, the city for which Tommy Rotwas developed, is located in the semi-autonomous region of South Tyrol, which was annexed by Italy from Austria. The city is still also known under its German name, Bozen. To a noticeable extent, people in the region speak both German and Italian. During the 1950s and ’60s, a South Tyrol independence movement often took on violent form. Taking all this into account, Yane invented a set of enactments based around the semi-fictional character of a 1960s Hollywood ‘wannabe’ actor-cum-South Tyrolean anarchist: Tommy Rot (Red Tommy). The enactments were made in collaboration with invited participants and casual passers-by, and with real-life media coverage.26

Tommy Rot, 2002, performative action in public spaces in Bolzano/Bozen (Italy), as part of the exhibition ‘To Actuality’ at ar/ge kunst. Photo: Angelika Burtscher

Calovski’s role in this work was that of the scriptwriter and stage director: the behind-the-scenes mastermind who lets the actress Patricia Pfeiffer appear throughout the city as a visibly distressed air hostess in a vintage Alitalia uniform.

Her character was looking for Tommy Rot (the word ‘tommyrot’ is actually from Thomas Moore’s Utopia and is an old idiom meaning ‘nonsense’) in the market, waiting for him at the Mussolini-era Liberation Monument (still fenced off after the separatist incidents to which Damianović refers), even attempting to jump from the bridge over the Adige/Etsch (or wade into its swift waters from the river bank) before being spotted at the bus station, attempting to leave town.

Tommy Rot, 2002, poster, 93 × 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist

The collaboration with the news media in Bolzano – RAI Uno for radio and television in Italian and ff Magazine for print coverage in German – was a crucial part of the work, which also exists in an exhibitable version consisting of video documentation and production photographs from the performances, press cuttings and a poster by graphic designer Manuel Raeder, based on a photograph by Calovski where Pfeiffer’s character seems to be fading into a haze.

Photographic documentation, by Robert Jankuloski, of Public Faculty No.1, project by Dutch artist Jeanne van Heeswijk organised by Press to Exit Project Space, 2008. Spreads from Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska (eds.), Think! Think! Think! Expanding the Present, Launching the Future. Skopje: Press to Exit Project Space, 2009

Fifteen years ago, when Calovski returned to Skopje, the city of his childhood and early adolescence, much had changed but the mini-wave of outside interest in contemporary art from Former Yugoslavia around the turn of the millennium had largely passed Macedonia by. He remembers:

I had seen enough of ‘the West’ – the US, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany – to know how the international art world functions, but also to be somewhat disillusioned by it. I often found this West nationalistic and protective of its privileges.

I wasn’t going to sit around waiting for invitations big enough to justify the sacrifice of being treated as the token representative of ‘my’ region.

But back then I also didn’t really know how to relate to the local context in Skopje, other than thinking: ‘it’s high time we get a place at the table; it’s all about representation.’

I was familiar with voluntary community organisation in the US, with the production residencies of the Fabric Workshop in Philadelphia, where I had worked as a student, and with the research practice and rhetoric of the CCA Kitakyushu and the Jan van Eyck Academie.

So I thought it would be meaningful to work from an essayistic, ephemeral, research-based starting point, but at the same time collectively, with the aim to build civil society, and to do this in Skopje, out of Skopje.

I also thought it would be meaningful to engage for a period exceeding the usual ‘sell-by date’ for an independent artist’s initiative. When something like this goes on for ‘too long’, it becomes more disruptive, more interesting.27

Photographic documentation, by Robert Jankuloski, of concert by Macedonian punk group FxPxOx organised by Press to Exit Project Space, 2008. Spread from Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska (eds.), Think! Think! Think! Expanding the Present, Launching the Future. Skopje: Press to Exit Project Space, 2009

Hristina Ivanoska had already been running Press to Exit Gallery in Skopje, with public funding from Switzerland, since 2002. When Calovski returned to Skopje in November 2004, she invited him to help reconstitute the gallery as ‘a programme-based artists’ initiative for research and production in the field of visual art and curatorial practice’.28

Press to Exit Project Space continued to get financial and infrastructural assistance from the Swiss Cultural Programme in Skopje until 2008, with Biljana Tanurovska-Kulakovski contributing her managerial expertise until 2006.

For the last twelve years this has been a self-organised venture, facilitating visual art projects, curatorial residencies and discursive and other events, as well as advocacy and policy initiatives within the cultural field and society at large. It is funded through various international collaboration projects and run by Calovski and Ivanoska in parallel with, and as a complement to, their individual and joint artistic practices. In recent years, the curator Jovanka Popova has also been associated with Press to Exit.

Poster for Wolfgang Tillmans‘s exhibition at Press to Exit Project Space, Skopje, 2005, 64 × 31 cm, Graphic design: Neda Firfova. Photo: Yane Calovski

The name might read as a tongue-in-cheek reminder that everyone needs an exit strategy, but actually it stems from the period of the physical gallery space, which was located within the security-conscious Swiss embassy and therefore had one of those ‘press to exit’ buttons at the front door.

Among the many programmes produced under their aegis, the exhibitions and public projects by Wolfgang Tillmans (2005) and Jeanne van Heeswijk (2008) deserve special mention, as do the residencies by curators Sebastian Cichocki (2005) and Başak Şenova (2006), the travelling project ‘Lost Highway Expedition’ (2006–2007), the lectures by artists Marjetica Potrč and Kyong Park (2004) and Jens Haaning (2008), curators Krist Gruijthuijsen (2006) and Joanna Warsza (2009) and the concert by the Macedonian punk band FxPxOx as part of ‘Future Perfect’, the last exhibition in Press to Exit’s own gallery space (2008).

Since 2009 Press to Exit has used more transient sites (rented flats, public parks, public institutions) for its continuedprogramming, carried out in partnership with similar organisations across Europe, increasingly with funding from various EU programmes. This way of working is likely to become more important in the years to come, with participatory governance set to become a cornerstone of North Macedonia’s negotiations for membership in the European Union.

Installation view of ‘Ponder Pause Process (A Situation)’ at Tate Britain, London, 2010. Photo: Joe Plommer and Matthew Blaney

The inclusion of Press to Exit in this last chapter of our appraisal may or may not stretch our legitimate understanding of what Maia Damianović wanted to achieve with her definition of ‘enactment’ as an act of artistic counter-intelligence.

Yet the ‘performative action’ that she propagated as a meaningful and purposeful artistic strategy through many of her curatorial projects may certainly serve as a definition of what Calovski did achieve in London in 2010.

As one of three artists, he was commissioned by Lucy Byatt, Head of National Programmes atthe Contemporary Art Society, which was celebrating its 100th anniversary, to choose works from the Tate Collection and display them in one of the exhibition halls at Tate Britain. He staged his intervention around the notion of performativity and titled it ‘Ponder Pause Process (A Situation)’.

Installation view of ‘Ponder Pause Process (A Situation)’ at Tate Britain, London, 2010, with works by Vito Acconci, Liam Gillick and Jeff Wall, as well as Yane Calovski’s U LAY, 2001/2010, cardboard, 200 × 60 cm (limited edition of 100 for Tate Britain). Photo: Joe Plommer and Matthew Blaney

Among the works he selected were Liam Gillick’s Big Conference Platform Platform (1998), which gestures towards a possibility for collective gathering, and Jeff Wall’s Study for ‘A Sudden Gust of Wind (After Hokusai)’ (1993), which insists on the highly scripted nature of a seemingly spontaneous situation. There was also Joseph Beuys’s Filzanzug (1970), a multiple in an edition of 100 which Calovski, in the catalogue for the project, characterises as driven by a wish to ‘return to the elementary understanding of self, sacrifice and spirituality’.29

When the life-size felt suit in its plexiglass box was to be hung, an otherwise hidden museum regulation revealed itself: no work can hang closer to the floor than 60 cm. Calovski seized on this and visualised the distance as a grey baseline encircling his exhibition. People would be able to come together, sit on the floor and lean against this protective layer of paint.